The "Slow-Death Camps” Are A Fact

Foreword

The "Slow-Death Camps” Are A Fact

By John Fraser

Fifty years ago this month, Canada — along with Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and France — declared war on Nazi Germany. The terrible confrontation took six years to reach its conclusion and claimed the lives of perhaps 50-million people, combatants and civilians alike.

Fifty years ago this month, Canada — along with Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and France — declared war on Nazi Germany. The terrible confrontation took six years to reach its conclusion and claimed the lives of perhaps 50-million people, combatants and civilians alike.

Unlike the "Great War" of 1914-18, the Second World War was imbued from the start with an air of righteousness that still strikes us as apt half a century later. Indeed this sense of a just war has been buttressed by post-war accounting, particularly as it brought home the reality of the German concentration camps where — notoriously — more than 6-million Jews were murdered in circumstances that will always cry out for remembrance and atonement.

Publisher's Note: we would challenge the fact that any Jews were systematically murdered under National Socialist German policy or by its administration or armed forces. We would also challenge the fact that more than a few hundred thousand Jews died on account of the war. - WRF

Postwar historians have properly complicated our understanding of how the war started. (The spinelessness of the Western democracies, for example, has long been seen as almost as crucial as the endemic German ills that gave rise to and sustained Nazism.) Nevertheless, ordinary people have never been in much doubt about the basics. It was Hitler's Germany that caused the war. In the terrible struggle to defeat the Nazis, most people could agree with Winston Churchill's famous witticism that even the devil would merit a favourable reference if he sided with the Allies.

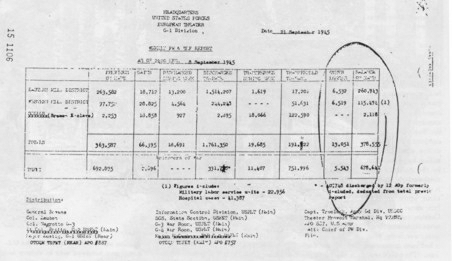

Time, though, plays perverse tricks. With this issue, and only coincidentally to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the war's outbreak, Saturday Night is publishing an oddity: an account of events born in the ashes of the Third Reich that no-one wants to publish — including ourselves. The reason is straightforward. The central revelation in James Bacque's report, which is adapted from his onerously researched new book entitled Other Losses, concerns the fate of German prisoners of war in the American camps in Europe in 1945 and 1946. The book itself implicates the French camps as well. By even the most conservative statistical reckoning, nearly a million prisoners died of starvation, exposure, and neglect at the hands of two of the victorious Allies. In the case of the Americans, this was accomplished; it needs to be stated very clearly, as a result of orders, issued from the highest levels of command that deliberately contravened the Geneva Convention on the treatment of POWs. The fate of the German POWs remained shrouded from scrutiny through a combination of self-deception and actuarial cover-up.

The fate of a million German POWs has remained shrouded from scrutiny through a combination of self-deception and actuarial cover-up

The fate of a million German POWs has remained shrouded from scrutiny through a combination of self-deception and actuarial cover-up

Forty years later, a rather quixotic and intense Canadian novelist with a knack for figures stumbled on the truth. His subsequent quest is detailed in a companion article commissioned from John Gault. Saturday Night was in on the latter part of Bacque's travails as he sought to find publishers for his astonishing story.

[As of August 10th, 2024, we have noticed that the website of James Bacque is now defunct. (https://www.jamesbacque.com/) Evidently, James passed on in 2019 at the age of 90. His book, Other Losses, is still available at Amazon.com.]

We were interested, but found it as hard as anyone else to accept the notion that such a catastrophe could have been hidden either at the time or later. In undertaking to publish a distillation of Bacque's findings, we worked with the eventual publisher of Other Losses, Stoddart Publishing, to ensure that his facts were independently verified and his manuscript scrutinized by relevant historical specialists. Some of Bacque's conclusions may be disputed — the precise significance of Eisenhower's name and initials on cables, for example, or the extent of premeditated orchestration behind the startling anomalies in POW statistics. But the cables and the anomalies themselves exist, and cannot be wished or argued away. Nor can the essential chronicle Bacque has pieced together of systematic and widespread deprivation of German prisoners in U.S. hands. The "slow-death camps" and the passive slaughter of probably a million Germans over the course of a few months are facts. To cavil at interpretations is to go on assisting in a camouflage.

In his book, Bacque has some pointed things to say about how, in the aftermath of the war, the Western media abdicated their responsibility to search out and publicize the truth. From inside the contemporary media world, we could tell a tale or two of our own: laziness, credulity, and a preference for avoiding complicated and unpopular controversies often contribute as much to successful cover-ups as all the theories of conspiracy put together. As things turned out, it was not so difficult to conic upon evidence of what went on inside the American and French death camps. What took hard work and perseverance to the point of obsession was untangling the sequence of events, investigating the political, military, and historical context, nailing down the culpability, and, of course, putting together the numbers — from a partial and edited record.

Not even a magazine that enjoys flirting with controversy from time to time is looking forward to the expected repercussions.

It was always understood that Bacque's revelations could and probably would be exploited by noxious elements in West Germany and elsewhere seeking to cancel guilt for the Holocaust and the war itself. Far stronger than this fear, however, was the sense of dismay that such a tale could have remained hidden for so long, and a sense of obligation to history.

One other thing needs to be said. Nothing in the revelations printed in Saturday Night mitigates in any way the historic culpability of the Nazi regime for its own crimes. The only possible way Bacque's story could do that would be if, in attempting to dismiss its significance, we were to cite the evil of the Nazis' policy of genocide as justification for the evil of maltreating prisoners of war. A summary paragraph in Other Losses underlines the essential point:

"Among all these people thought to be of good will and decent principles, there was almost no-one to protect the men in whose starved flesh was our deadly hypocrisy. As we celebrated the victory of our virtue in public, we began to lose it in secret."