Justifying the National Socialist Reaction to the Reichstag Fire, Part 1 - Threat of Communist Revolution in Germany, 1929-1933

Previous Website Downloads

What follows are book excerpts and notes which were prepared for this presentation.

The Threat of Communist Revolution in Germany, 1929-1933

In order to understand why the National Socialists would immediately believe that the Reichstag Fire was a Communist plot, one must understand the extent to which Communist Revolution was a threat all throughout the post-war period of Weimar Germany. Here that shall be made evident, from a rather liberal academic who has a clear bias against the Nazis. For reason that this author, Dietrich Orlow, has a clear antipathy for National Socialism, we have chosen this source in order to make our presentation.

This section is quoted from the book, Weimar Prussia, 1925-1933, The Illusion of Strength by Dietrich Orlow

From Chapter 3, Innenpolitik: Security Matters, Personnel Policies, Administration, and Church-State Relations

The state was determined to create a police force that could deal effectively with outbreaks of political violence by all antirepublican forces. Prussia's goal was a well-organized, well-paid, and politically reliable police force that would also be kept free of interference by the Reich. The state's municipal police chiefs were the only group of top officials in Prussia that contained a large number of Aussenseiter (literally "outsiders"; the American technical term is "lateral entries"), which did not sit well with some of the champions of "professionalism" among the state's leaders ("Outsiders" were officials who lacked the administrative law degree that was the traditional prerequisite for a high-level civil service career in Prussia.) Ten of the thirteen municipal police chiefs appointed after August 1925 were Aussenseiter; for the most part former labor union officials. Prussia also kept ties between its police forces and the Reichswehr to a minimum. Prussian police legislation precluded the routine transfer of army veterans to positions in the state police, a practice that had been traditional in Prussia before 1914 and continued to a lesser extent even after the revolution. Similarly, the state resisted any efforts by the Reich authorities to subject the state's police forces to the control of the Reichswehr during times of declared states of emergency. It was not surprising that the state's personnel policies for its police forces evoked a cry of indignation from the German Nationalists

Although the Reich authorities would later charge that Prussia's concern with right-wing extremism and the state's unwillingness to cooperate with the Reichswehr in internal security matters meant that the state's security experts were blind to the Communist danger, the Prussian authorities for a long time actually underrated the fascist threat, and overestimated the Communists' strength.

[The author's claims concerning this throughout this chapter seem to reflect his anti-Nazi bias, eg. the Nazis gained power, so the “threat” must have been underrated. There is no evidence of particular instances of “right-wing” violence offered in this chapter by the author. He seems to be a leftist offering generalities which demonize the right. He also perceives National Socialism as right-wing, although in reality it is neither right nor left. National Socialism transcends the right-left political paradigm.]

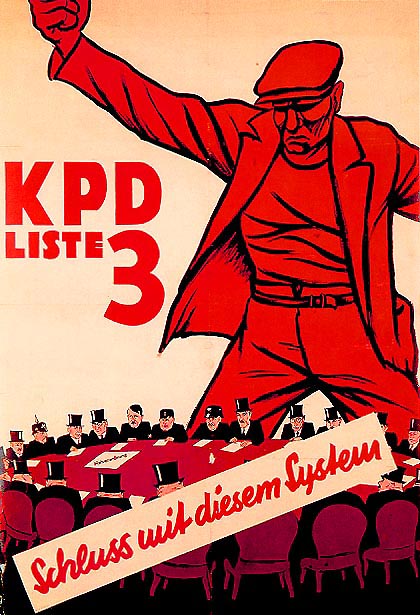

Both Prussian and Reich officials gave excessive credence to the Communists' own boasts. As we saw, in the years after 1925 the KPD underwent massive internal upheavals. The final result was the party's subjugation to Stalin and the Comintern, but before the party's stalinization was complete, left, right, and center factions attempted to prove to the KPD's Russian masters as well as to the party's rank-and-file members that their particular strategies could bring about the long-delayed Communist revolution in Germany.

A key factor in evaluating the danger of a Communist coup was assessing the strength of the KPD's own paramilitary organization, the Rote Frontkampferbund (RFB). Founded in 1925, the RFB had a membership of several thousand, but opinions differed widely about its discipline and combat readiness. The Reich government argued that the RFB was a genuine threat to law and order, while the Prussian authorities regarded it as a blustering, but not acutely dangerous organization. Almost as soon as the RFB was founded, the Reich minister of the interior demanded that Prussia prohibit the RFB throughout the state, but Severing and Grzesinski both felt it was sufficient to keep a close watch on the organization. They only moved against individual locals when, as was true in Dortmund, the police found that the RFB maintained stores of illegal weapons

However, by 1928 there was increasing evidence that ultraleftist elements in the KPD were using the RFB as a part of their strategy of provoking street violence to create what they regarded as a protorevolutionary situation. The Prussian interior ministry planned to restrain the RFB's activities in the spring of 1928. However, tactical considerations delayed action: the Prussians felt that moving against the RFB just before the upcoming national and state elections would give the Communists an additional campaign issue.

In view of what was to come, the delay was unfortunate. In the fall and winter of 1928-29, the KPD's ultraleft wing, disappointed by the failure of the strategy of "union from below" to weaken the SPD, felt that spectacular action was needed both to impress the Comintern councils and to demonstrate to the Social Democrats that the German Communists were still a force to be reckoned with. Communist violence culminated in a series of riots in Berlin in May 1929. The KPD had applied for permission to stage one of their traditional May Day demonstrations in the capital. The Berlin chief of police at the time, Karl Zorgiebel (SPD) feared the demonstrations would lead to violence and prohibited the march. The Communists deliberately and openly ignored the ban. The police chief was determined to meet what he regarded as a direct challenge to law and order. Fully supported by the Prussian ministry of the interior, Zorgiebel ordered the police to use massive force in breaking up the Communist demonstrations. The result was a bloody altercation between the police and the demonstrators in which more than a dozen people lost their lives. Immediately afterwards the ministry ordered the dissolution of the RFB throughout Prussia.

The political wisdom and long-range consequences of these events are not easy to assess. The Berlin police and the Prussian ministry of the interior assumed that the Communists planned the riots as a direct provocation of the Prussian government, and the Communists' open talk about the final armed battle with capitalism seemed to support such an interpretation. On the other hand, verbal posturing was a familiar KPD propaganda tactic. It was often intended more for intraparty consumption than to launch concrete activities. [Again, the author sounds like a leftist apologist.] It is also true that after the prohibition of the RFB there was a decline in the level of large-scale Communist violence in Prussia, but it remains unclear if the state's decree was cause or coincidence. The KPD's ultraleft phase had probably reached its end in any case. [Nonsensical conjecture.] Recent research has demonstrated that the Prussian authorities and especially Zorgiebel as police chief were not without blame in creating the situation; the Berlin police's handling of the May Day demonstrations showed all the classic symptoms of overreaction and unnecessary violence.

There is no doubt, however, that Zorgiebel's and Grzesinski's reaction to the May demonstrations plunged relations between the Communists and the Social Democrats to new levels of bitterness and animosity. While the Social Democrats professed to have a "clear conscience" about the May Day actions, for the Communists these events became the "bloody May." The Communists described Zorgiebel as the "Mussolini of Berlin" and Grzesinski as the "murderer of the workers.” On the eve of new challenges from the extreme right, the left was more divided than ever.

[These challenges are not described by the author as having come from National Socialists.]

In their handling of the right-wing extremists the Prussian authorities concentrated far too long on the danger of a new putsch. There ministry of the interior was convinced that various groups were planning a new coup, although the officials also recognized that dissension and ineffective leadership prevented any of the pseudo-military formations from launching another putsch, at least for the moment. Nevertheless, Prussia remained vigilant. The state's authorities were especially nervous since they were convinced that in the battle against right-wing extremism they were essentially on their own. Little help could be expected from either the civilian or the military agencies in the Reich. On the contrary, the Reich interior ministry all but sabotaged Prussia's efforts to suppress the activities of the antirepublican right.

[The author goes on to discuss the banning in Prussia of an extreme-right party called the Wikingbund, and the desire and initiative towards rearmament undertaken by certain elements of the Wehrmacht. He only mentions National Socialists several pages later where discussing government employee salaries and the poorly-compensated municipal employees he says “Local officials' resentment because of the cuts that began in 1930 was one of the reasons for the high proportion of Nazi sympathizers among municipal employees.” So the KPD has a paramilitary branch, relations with Stalin, and plans to overthrow the Reich, but the evil Nazis may tend to raise the salaries of town clerks.]

From Chapter 5, The German Parties and Prussia, 1930-1933

In this chapter the author describes the political parties of Weimar Germany

The largest of the Prussian opposition parties [opposed to the Weimar coalition led by the Social Democrats (SPD)], the DNVP [German Nationalt People's Party], had consistently rejected parliamentary democracy as a constitutional system ever since the revolution of 1918. Despite mounting evidence that its obstructionist policies [here the author reveals his own leftist leanings, by calling anti-democrats “obstructionist”] hurt the party, the DNVP blindly followed this course to the end, resolutely refusing to function as a loyal opposition [the author upbraids them for sticking to their principles, for refusing to play the game]. Rejecting the advice of some moderates in its ranks, they continued to pursue the dream of restoring Prussian authoritarianism.

Orlow proceeds by explaining how the German National People's Party by the mid-1920's did indeed adopt a rather mainstream conservative role in Weimar politics, but that eventually it and all of the “conservative splinter groups” were absorbed by the National Socialists. Hitler's philosophy would certainly seem a natural for the Prussian conservatives. Orlow then explains how the DNVP alienated another Prussian opposition party, the Catholic Center Party, in a dispute over relations with the Vatican. Then he says:

In contrast, the DNVP accepted the Nazis as full-fledged partners of the "national right." Although some DNVP members told Otto Braun privately of their misgivings about the emerging partnership, it became increasingly difficult to distinguish the programmatic positions, parliamentary tactics, or political rhetoric of the two parties. Not even anti-Semitism distinguished them as the DNVP's speakers in the Landtag became increasingly open in their attacks on Jews.

With this, Orlow describes once again the DNVP's disenchantment with and lack of participation in the parliamentary democracy. He also describes anti-Semitism within the rather mainstream DNVP, and therefore we see that anti-Semitism in Germany did not start with nor was it limited to National Socialism. He concludes that Prussia's “German Nationalists would serve as junior partners of the Nazis in order to see the hated system of political democracy destroyed.”

Next, describing the National Socialists, he says that “The NSDAP competed with the KPD for leadership of the 'revolutionary opposition.” But Orlow never attributes violence against the State or its government to the NSDAP, not once, even though he betrays his antipathy for the Nazis rather consistently, with statements such as one where he discusses their budding support and he says that “signs of the Nazi's corrosive effect on some segments of German society had been evident for some time (the explosive growth of the Nazi student movement, for example, clearly indicated the movement's inroads among middle-class Germans)”.

After detailing NSDAP success in elections in 1929 and 1930 Orlow does claim that “Nazi-generated street violence rose unabated throughout 1931 and 1932” but he never substantiates that claim. He only describes “friction between the storm troopers and the political cadres”, and does not immediately tell us what “political cadres” they fought with. Then he claims that in 1932 Goebbels was the master of plans to provoke the Communists into attempting a putsch so that the Nazis could appear as if they had prevented a Bolshevik coup. However the only violence that Orlow could rightfully attribute to the Nazis were their fights with the Communists, where he says that “to Goebbels' delight, in late May Nazi and Communist delegates fought a pitched battle in the halls of the Landtag” [the Prussian parliament].

Describing the Communist Party (KPD), Orlow compares it to the National Socialist party and describes their similarities by saying that “Its penchant for street violence equaled that of the Nazis. Both the KPD and the NSDAP saw themselves as 'antiparties,' and in a very real sense each justified its own self-image by referring to the actions and ideology of the other.” Here Orlow seems to completely - and perhaps purposely - miss the facts that the existence of the National Socialist party could be attributed firstly to a reaction against the decadence of Germany under Weimar, and secondly to a need for a bulwark against Communism. He also ignores the fact that most Nazi street violence was against the aggression of the Communists.

Orlow says that “The Nazis claimed that only they could save Germany from the Bolshevik revolution, while the KPD looked upon the Nazis as evidence that the last crisis of German capitalism was at hand and the proletarian revolution just around the corner”. But he infers that the Nazi claims concerning the Communist threat, and the Communists' own boasts, are exacerbated and that the Communist threat to revolution really did not exist at all.

Then Orlow describes condition of the Communist Party in these crucial years as one of misdirection and fractured leadership:

But there were also profound differences between the two extremist parties. The intraparty struggles in the NSDAP concerned only German issues, while those among the Communists were closely related to the battles for power in the Soviet Union and control of the Comintern among Lenin's successors. The Nazis had a surfeit of Prussian strategies, but the Communists never developed a separate strategy for getting to power in the state. The correct party line in Prussia was merely one of the issues that fueled the chronic intraparty factional disputes rocking the KPD.

Despite some significant tactical shifts between 1929 and 1933, the KPD generally followed a leftist or ultraleftist course. In both leaders and strategy, the German Communists were closely allied with the Zinoviev faction within the Comintern leadership in Moscow. Heavily dependent on the Comintem for both ideological guidance and financial support, the KPD faithfully followed the Comintern's "social fascism" line. According to this concept, some of whose most enthusiastic proponents were Communist members of the Prussian Landtag, the KPD identified the SPD (Social Democrats) rather than the Nazis or the DNVP (Prussian conservatives) as the spearhead of fascism and capitalist reaction in Germany. The communists were slow to recognize the Nazi danger, arguing well into the 1930s that the NSDAP was less dangerous than the "social fascist" SPD and the Prussian government that party dominated. Consequently, Communist theoreticians argued that the destruction of the SPD as the last real pillar of capitalism was a prerequisite for the collapse of the capitalist system as a whole and inauguration of the Communist revolution that would inevitably follow. It is ironic that after months of intraparty wrangling (which concerned personality clashes more than disagreements over strategy) the victory of the ultraleftists and their doctrine of social fascism was complete just a few weeks before Hitler became chancellor.

Despite some significant tactical shifts between 1929 and 1933, the KPD generally followed a leftist or ultraleftist course. In both leaders and strategy, the German Communists were closely allied with the Zinoviev faction within the Comintern leadership in Moscow. Heavily dependent on the Comintem for both ideological guidance and financial support, the KPD faithfully followed the Comintern's "social fascism" line. According to this concept, some of whose most enthusiastic proponents were Communist members of the Prussian Landtag, the KPD identified the SPD (Social Democrats) rather than the Nazis or the DNVP (Prussian conservatives) as the spearhead of fascism and capitalist reaction in Germany. The communists were slow to recognize the Nazi danger, arguing well into the 1930s that the NSDAP was less dangerous than the "social fascist" SPD and the Prussian government that party dominated. Consequently, Communist theoreticians argued that the destruction of the SPD as the last real pillar of capitalism was a prerequisite for the collapse of the capitalist system as a whole and inauguration of the Communist revolution that would inevitably follow. It is ironic that after months of intraparty wrangling (which concerned personality clashes more than disagreements over strategy) the victory of the ultraleftists and their doctrine of social fascism was complete just a few weeks before Hitler became chancellor.

Orlow later asserts that the Communists could not be any real threat to the German State where he says “At the beginning of 1932, the [Communist] party was in the midst of a major crisis. The KPD came under the control of increasingly opportunistic and 'infantile' elements. Incapable of launching a revolution, unable to persuade most German workers to desert their traditional allegiances, and blind to the real menace of the Nazis, the KPD wallowed in verbal radicalism.”

While perhaps it was Providential that during these years the Communists may have been incapable of launching a real revolution, in his next chapter, Chapter 6, Orlow shows that the German government in the last years of the Republic did not share that opinion.

From Chapter 6, Prussia and the Depression: Innenpolitik During the Republic's Final Years, 1930-1933

While in chapter 5 in his description of the condition of the Communist Party (KPD ) in the final years of the Republic, Orlow attempted to downplay Communist capability for revolution, and to depict the Nazis as having exacerbated the threat, here he informs us that the German State saw a Communist Revolution as a far more pervasive danger. The following text from pages 185-187 of his book begins with the conclusions concerning a debate in the Prussian legislature over whether the NSDAP should be banned in Prussia. Assessing this, we must not forget that Prussia's government was dominated by Social Democrats, who had the most to lose if the DNVP or NSDAP ever came to power [my comments are in brackets]:

Legally, the Reich cabinet's differing assessment of the Nazis did not prevent Prussia from taking vigorous action of its own, but there is little doubt that Bruning's appeasement policies seriously discouraged those in Prussia (and some other Lander) who wanted to move against the Nazis. The state officials lamented that since the Nazis were organized throughout the country, prohibiting the party in one state would simply mean that Hitler's movement would transfer its operations to other Lander. But there was a persuasive counterargument: if, as the Prussians had always argued, control of Prussia meant control of Germany, then making things difficult in Germany's largest state would have meant a serious weakening of the Nazi movement. Instead, after the summer of 1930 Prussia allowed the initiative in the battle against political extremism to slip out of its hands.

Prussian interior ministry officials were concerned with the threat posed by the Nazi storm troopers, but they were almost as worried about another far right paramilitary group, the Stahlhelm. For many contemporaries, the Stahlhelm seemed both ready and able to stage a putsch of its own. It had a membership of almost 5 million, its leadership corps was composed primarily of former career military officers, and it was closely linked to the DNVP, the Reichswehr, and the Nazis. In retrospect, fears of the Stahlhelm putsch appear groundless; despite its impressive numbers, and combat-simulating activities (including nighttime "maneuvers"), the Stahlhelm, like the Communists' paramilitary organization, was a paper tiger. [This is Orlow's opinion concerning the Communists.]

Even more than in the case of the Nazis, Reich [The German federal government] and state [meaning Prussia] took entirely different approaches to Stahlhelm activities. The veterans' organization had powerful friends in high places, notably the Reich president, its honorary national chairman. Moreover, Hindenburg interpreted his Schirmherr (protector) role quite literally: at the request of the Stahlhelm's leaders he intervened openly to protest Prussia's moves against "his" organization. Since it was virtually impossible to coordinate actions with the Reich government, Prussian authorities once again watered down their planned moves against the organization (which included a total prohibition of the Stahlhelm's paramilitary activities and uniformed demonstrations) in order to avoid friction with the Reich government.

The Prussian and Reich governments also had far different views of the threat from the extreme left, the Roter Frontkampferbund (Red Front Fighters' Association, RFB). Prussian authorities certainly recognized the RFB's violent character. According to Prussian statistics, it was involved in about as many instances of political violence as the Nazi storm troopers, since the two organizations often attacked each other. Severing and Abegg, however, doubted (accurately) that the RFB was capable of staging a coup or starting the "revolution" that was a constant theme of the organization's rhetoric. The Reich government, however, argued as it had since the 1920s: the RFB was a far more serious threat to law and order than the [Nazi] storm troopers or the Stahlhelm. The result was more friction between Reich and state. Federal authorities again urged the Prussian government to order the dissolution of the RFB. (As we saw, Prussia had prohibited the RFB for a time after the May 1929 Berlin riots.) When the state refused, the Reich cabinet accused Prussia of being soft on Communism.

We presented Orlow's description at the beginning of this presentation, that after the May 1929 Communist riots in Berlin the RFB was banned. Here it is apparent that the SDP in Prussia must have been schizophrenic, or perhaps infiltrated by Communist agents, or perhaps Orlow is making some sort of misrepresentation somewhere. In his description of the German political parties, Orlow described the bitterness that existed between the Communists and the Social Democrats who controlled the Prussian government through the end of the Weimar era, and described how the KPD saw the SPD as an enemy even greater than the Nazis.

Yet here we see that the SPD and the Prussian government were after 1930 refusing to ban the KPD's paramilitary branch, the RFB. The KPD was being funded by Moscow, as Orlow here describes, and it had its primary allegiance to the Soviets in Russia, and it had an active paramilitary organization inside Germany, the RFB. Additionally, there were countless threats of Communist revolution, countless skirmishes between Nazis and Communists, and the Communists had a long history of violence against the State, something the Nazis were not accused of since the days of the beer hall putsch in Munich (and even there the allegation was a false one).

The only reasonably valid conclusion to all of this in relation to the burning of the Reichstag is that the Communist threat of violent revolution was still very real in the first months of the Hitler government, and Hitler had every reason to suspect a Communist hand in the act.

Here are some KPD election results, to show that they indeed had support among the people, and ten percent is plenty enough to provide the ability to launch a violent attempt at power. The Bolsheviks began with far less than that.

In 1920, shortly after the "Spartacist uprising", the KPD had won just 4 seats in the federal parliament; . In 1924, the Communist Party had increased its share of the vote to 12.6% and captured 62 parliamentary seats.

The vote gotten by the Communist Party (KPC) 1928-1933:

Election of May 20th 1928: the KPD won 10.6% of the vote and 54 seats in the Reichstag.

Election of September 14th 1930: the KPD won 13.1% of the vote and 77 seats in the Reichstag.

Election of July 31st 1932: the KPD won 14.6% of the vote and 89 seats in the Reichstag.

Election of November 11th 1932: the KPD won 16.9% of the vote and 100 seats in the Reichstag.

Election of March 5th 1933: the KPD won 12.3% of the vote and 81 seats in the Reichstag.

From Hitler, Democrat: Chapter VI, Part 3 – The Social Revolution by General Leon DeGrelle, an article excerpt from his book which appeared in the June 1996 issue of The Barnes Review:

The German Marxists had always been very intolerant. They had never conceded liberty to anyone but themselves. The Rote Fahne of 30 May 1920 wrote in so many words: “The proletariat claims for itself the liberty of assembly. It must be denied to its enemies.” [This is something the Marxists put to practice by attempting to violently interrupt all meetings of their political rivals throughout the Weimar years, which necessitated the development of the SA in the NSDAP.]

Anyone who did not think like the Marxists was a heretic.

The world bastion of Marxism, the USSR, has proven it a thousand times. Whether it was a question of the doctrinaire Lenin of 1917 or the brutal Stalin, victor in the Second World War, anyone who was not in accord with them found himself in the cellars of the Cheka, or perhaps admiring Russian scenery from the top of a gibbet, or eating rats caught at night in the latrines of a frozen camp in the Siberian wilderness.

And Hitler committed the crime not only of not being a Marxist but of being fundamentally anti-Marxist by resorting to the very tactics of Marxism.

As a matter of fact, the fury of the Reds didn't trouble him at all. He even lay in wait for them to provide proof that the rule of terror had come to an end, that he was firmly determined to oppose Marxist terrorism with an implacable counterterrorism as the only real solution if loyal citizens were to be permitted to live free.

To submit to the law of the hoodlums was to give up defending liberty.

You don't extend your hand to enemies like that, as so many simpletons do these days: You use their own methods and put them out of their misery.

So today liberal useful idiots write books describing the SA stormtroopers (who were the defenders of German tradition) on the same level as the Marxist hoodlums (who actually represented foreign interests) who they had the nerve to stand and oppose. However regardless of his bias against those evil Nazis, even Orlow could not entirely mask the fact that there was a threat of communist revolution in Germany right up to when the National Socialists had come to power.