- Operation Barbarossa

Previous Website Downloads:

February 6th, 2011

David Irving, Hitler's War

I have not read much of Irving's work, but today I perused parts of Hitler's War, which I have some excerpts from here. It seems to me that Irving displayed a very typical Anglo bias against Hitler. At least 10 times in the book he portrays Hitler's top aides as his “henchmen”, and calls the German leadership an authoritarian military dictatorship, even in contexts as early as 1940. In his introduction he also accepts the historicity of a holocaust and blames it not on Hitler, but on “a large number of Germans … many of them alive today”.

There is also another long statement in Irving's introduction which I find confusingly wrong: “Being a modern English historian there was a certain morbid fascination for me in inquiring how far Adolf Hitler really was bent on the destruction of Britain and her Empire – a major raison d’etre for our ruinous fight, which in imperceptibly replaced the more implausible reason proffered in August , the rescue of Poland from outside oppression.” Yet Irving mentions Hitler's “unwillingness to humiliate Britain when she lay prostrate in ”, and very often quotes from or refers to Mein Kampf, where it is clear both in action and earlier in word that Hitler never wanted to destroy Britain. For these reasons, I see Irving as little more than another court historian, even though he had an epiphany concerning the fallacy of the claims concerning gas chambers.

From the chapter The Barbarossa Directive

Irving deals with this topic from the perspective of the diplomatic exchanges between Molotov and Hitler, but from what I have seen so far, he does not seem to be aware of the plans that Stalin already had in place, as we saw from Suvorov, for an offensive assault on Germany and Europe. In fct, Irving goes so far as to state on page 346 that “Before ten days had passed, it became even more evident that the Russians’ aims were irreconcilable with Hitler’s to which I might reply “well, no kidding!”

pp 349-350

Molotov’s negative reply to Hitler’s proposals at the end of November dispelled whatever hesitations he still had about attacking Russia. Visiting the sick Fedor von Bock again briefly on December , the field marshal’s sixtieth birthday, Hitler warned that the ‘eastern problem’ was now coming to a head. This in turn made a joint Anglo-Russian enterprise more likely: ‘If the Russians are eliminated,’ he amplified, ‘Britain will have no hope whatever of defeating us on the Continent.’ To Brauchitsch, two days later, Hitler announced, ‘The hegemony of Europe will be decided in the fight with Russia.’

Thus his strategic timetable took shape. He would execute the attack on Greece (code-named ‘Marita’ after one of Jodl’s daughters) early in March . Of course, if the Greeks saw the light and showed their British ‘guests’ the door, he would call off ‘Marita’ altogether – he had no interest whatever in occupying Greece. Then he would attack Russia during May. ‘In

three weeks we shall be in Leningrad!’ Schmundt heard him say.

Virtually nothing was known about the Red Army: a complete search of archives in France – Russia’s own ally – had yielded nothing. Hitler was confident that the German Mark III tank with its -millimetre gun provided clear superiority over the obsolete Red Army equipment; they would have , of these tanks by spring. ‘The Russian himself is inferior. His army has no leaders,’ he assured his generals. ‘Once the Russian army has been beaten, the disaster will take its inevitable course.’

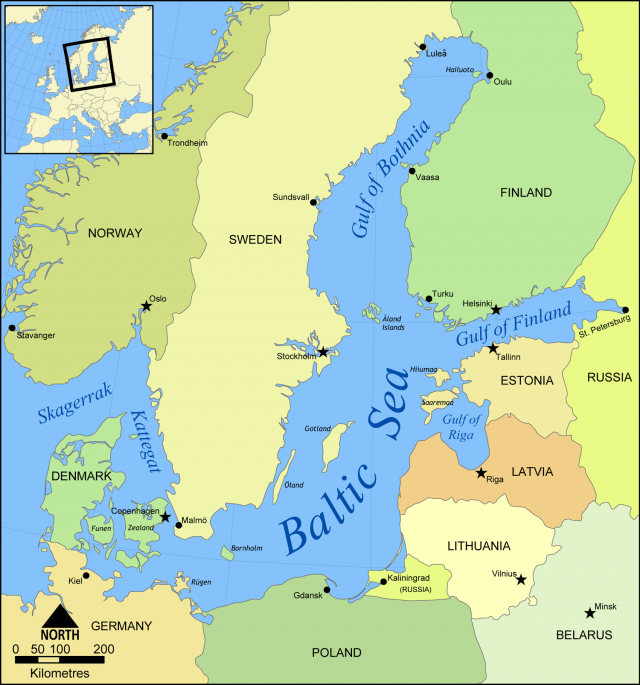

At three P.M. on December , Hitler’s military advisers came to the chancellery to mull over each phase of these coming operations. Now for the first time the two varying concepts of the Russian campaign were brought into informal synthesis. Halder’s General Staff proposal was distinguished by a particularly powerful main drive toward Moscow. Lossberg’s OKW study ‘Fritz’ attached more weight to the northernmost army group and the occupation of the Baltic coast; in his reply to Halder the Führer now drew heavily on Lossberg’s arguments.

Both Halder’s plan and Lossberg’s assumed that the Russians must of necessity defend the western areas of the Soviet Union and the Ukraine; and both stated that the Russians must be prevented from staging an orderly retreat as in . The army and OKW were also agreed that they must occupy as much Soviet territory as necessary. This would prevent the Russian air force from reaching Reich territory. Halder proposed that the offensive end along a line from the Volga River to Archangel.

Where Hitler took exception was to Halder’s insistence that nothing detract from the main assault on Moscow. Hitler wanted the Russian forces in the Baltic countries to be encircled first; a similar huge encirclement action by Army Group South, south of the Pripyet Marshes, would liquidate the Russian armies in the Ukraine. Only after that should it be decided whether to advance on Moscow or to bypass the Soviet capital in the rear. ‘Moscow is not all that important,’ he explained. When the first draft directive for the Russian campaign was brought to Hitler by Jodl, it still conformed with Halder’s recommendation of a main thrust toward Moscow (‘in conformity with the plans submitted to me’). Hitler however ordered the document redrafted in the form he had emphasised: the principal task of the two army groups operating north of the Pripyet Marshes was to drive the Russians out of the Baltic countries. His motives were clear. The Baltic was the navy’s training ground and the route which Germany’s ore supplies from Scandinavia had to take; besides, when the Russians had been destroyed in the Baltic countries, great forces would be released for other operations. The Russian campaign must be settled before was over – for from onward the United States would be capable of intervening.

Toward the United States Hitler was to display unwonted patience despite extreme provocations for one long year. American nationals were fighting in the ranks of the Royal Air Force, and United States warships were shadowing Axis merchant ships plying their trade in transatlantic waters. The admiralty in Berlin knew from its radio reconnaissance that the Americans were passing on to the British the information about these blockade runners. In vain Admiral Raeder protested to Hitler about this ‘glaring proof of the United States’ non-neutrality.’ He asked whether to ignore this was ‘compatible with the honour of the German Reich.’ Nothing would alter Hitler’s determined refusal to take up the American gauntlet. Nor

would he be side-tracked into invading England.

In a secret speech to the gauleiters on December he declared the war as good as won, and assured them that ‘invasion [is] not planned for the time being.’ ‘Air supremacy necessary first,’ concluded Dr. Goebbels afterwards in his diary, and added his own one-word comment on Hitler’s psychoses: ‘Hydrophobia’ – Hitler had an aversion to carrying any military operation across the seas; he had also shrewdly refrained from revealing to Dr. Goebbels his plan to attack the Soviet Union. ‘He’s frightened of the water,’ Goebbels recorded after again speaking to Hitler on the twenty-second about invading England; to which he added: ‘He says he would undertake it only if he was in the direst straits.’

Unbeknownst to the propaganda minister, Hitler’s eyes were fastened upon Russia. On December , Jodl brought him the final version of the campaign directive, retyped on the large ‘Führer typewriter.’ It had been renamed ‘Barbarossa.’ Partly the handiwork of Jodl, whose spoken German was very clear and simple, and partly the product of Hitler’s pen, the eleven-page document instructed the Wehrmacht to be prepared to ‘overthrow Soviet Russia in a rapid campaign even before the war with Britain is over.’ All preparations were to be complete by mid-May .

From p 359:

This might be one consequence of the German capture of the Ukraine, Moscow, and Leningrad, replied Hitler; otherwise the Wehrmacht must advance toward Yekaterinburg. ‘Anyway,’ he concluded, ‘I am glad that we carried on with arms manufacture so that we are now strong enough to be a match for anybody. We have more than enough material and we already have to begin thinking about converting parts of our industry. Our Wehrmacht manpower position is better than when war broke out. Our economy is absolutely firm.’

The Führer rejected out of hand any idea of yielding – not that Bock had hinted at it. ‘I am going to fight,’ he said; and ‘I am convinced that our attack will flatten them like a hailstorm.’

Two days later Field Marshal von Brauchitsch brought Chief of General Staff Franz Halder to the chancellery to outline the army’s operational directive on ‘Barbarossa.’ Although army Intelligence believed the Russians might have as many as , tanks, compared with their own ,, the Russian armoured vehicles were a motley collection of obsolete design. ‘Even so, surprises cannot be ruled out altogether,’ warned Halder. As for the Russian soldier, Halder believed the Germans were superior in experience, training, equipment, organisation, command, national character, and ideology. Hitler naturally agreed. As for Soviet armament, he was something of an expert on arms production, he said; and from memory he recited a ten-minute statistical lecture on Russian tank production since .

Hitler approved the army’s directive, but once again he emphasised the capture of the Baltic coast and of Leningrad. The latter was particularly important if the Russians were falling back elsewhere, as this northern stronghold would provide the best possible supply base for the second phase of the campaign. Hitler knew that Halder had just had a first round of talks with his Finnish counterpart, General Erik Heinrichs, in Berlin. He was convinced the Finns would make ideal allies, although Finland’s political strategy would be problematical as she wished to avoid a complete rupture with the United States and Britain. As he said to his staff, ‘They are a plucky people, and at least I will have a good flank defence there. Quite apart from which, it is always good to have comrades-in-arms who are thirsting for revenge. . .’

It seems to me that Irving was totally unaware of the necessity for Hitler to act against the Soviets, out of a desire to defend Europe against the onslaught of the mongol hordes against Christendom which was planned by Stalin. Rather, Irving portrayed Hitler as a cavalier thug, typical of a historian who swallowed the jewish kool-aid.